There is no question more important than that which Jesus asked his disciples (Mt 16:15): “Who do you say I am?”No topic has been debated more intensely, totally and partially misunderstood, ignored with great risk and correctly answered with a correct answer to this question is, in a way, simple enough to save a child, but also complex enough to occupy theologians for eternity. If eternal life is knowing Jesus Christ (John 17:3), then can we not afford to ignore the one who is the most distinguished among ten thousand?(Ct 5. 10).

Peter confessed jesus as the Christ, the Son of the living God?(Mt 16:16). John spoke of Jesus as “the Word?” This flesh was made (John 1:14). Paul describes Jesus not only as “the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation?”(Colossses 1:15), but also as Christ Jesus, man? (1 Tim 2. 5). Similarly, the author of Hebrews identifies Jesus as much as “the glare of glory?”(Heb 1. 3) of God and like the one who participated in the flesh and blood (2. 14). After touching Christ, Thomas memorably confessed jesus as his ?Sir? And you, God?(Jn 20:28). In the Old Testament, Isaiah had a vision of Christ in what he calls: the king, the Lord of armies?(Jn 12:41; see Is 6. 5), but he also called this king a servant of the Lord, who had no beauty to please us?(Is 53. 2).

- Jesus also had much to say about himself.

- In the Gospel of John.

- The place of the well-known declarations of the “I am”.

- He refers to himself as the “pain of life” (Jo 6:48).

- “the light of the world?”(8.

- 12).

- ?The door? (10.

- 9).

- ?The good Shepherd? (10.

- 11).

- “Resurrection and Life” (11.

- 25).

- “Way.

- Truth and Life” (14.

- 6) and “The True Vine” (15.

- 1).

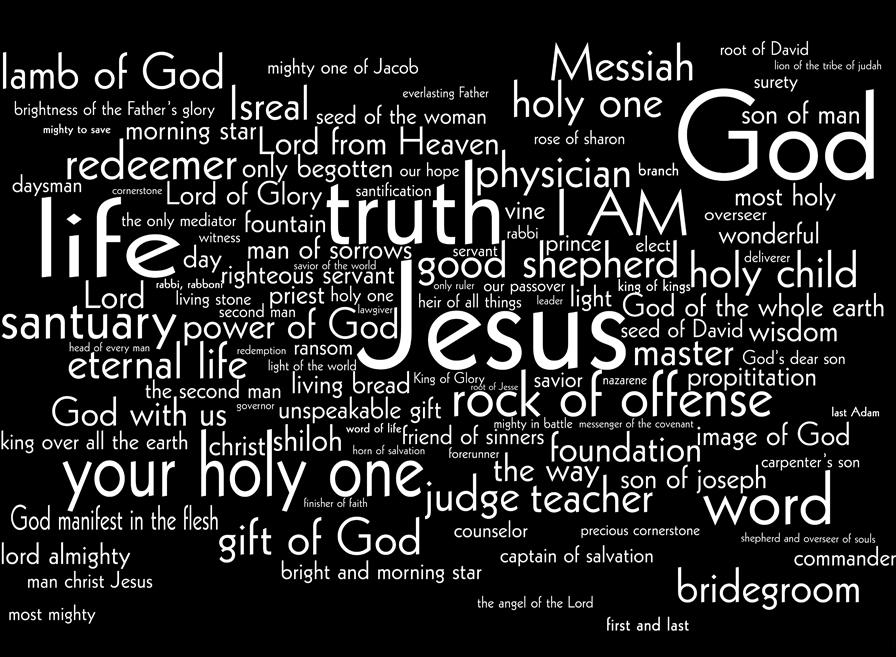

In other passages, Jesus is called Master (M. 1. 27), Prophet (Mt 21:11), Son of David (9. 27), Servant (12,18), Son of Man (12. 8), Lord (14,30), Lamb of God (John 1. 36), Holy Of God (6. 69), The Principle (Cl 1. 18), High Priest (Heb 5. 1-10), the Living (Ap 1. 18), Liberator (Rom 11. 26) and the Lucero of the Morning (P 22:16).

Many more could be added to this impressive variety of biblical names and descriptions; In fact, much more than we can think or imagine; However, these multiple statements by the person of Christ are not always easy to understand; in fact, the early Church fought long before reaching a concise and precise description of the person of Christ in the Council of Chalcedon (451 AD).

Every century, since the time of our Lord and the Apostles, he has witnessed one or more atypical visions of Christ. Without being thorough, at the end of the 1st century the error of dotticism left its mark. The idea that jesus’ flesh was “spiritual” was Serapio, Bishop of Antioch (190-203). Jesus did not have a true human nature, it simply seemed (in Greek: dokeo, “Does it seem?) Human. This false vision was defended by some, though the Apostles were still alive (2 John 7).

In the 2nd century, the Erionites (“the poor”) rejected the blank conception of Jesus. They considered him the Messiah, but they did not accept that he was divine.

At the beginning of the 3rd century Paul de Samsata, bishop of the church of Antioch (around 260), was born, who had a particular vision of Christ, who embodied several heresies, for him Jesus was an ordinary man inhabited by the Logos (Verb) and thus became the Son of God. The Logos that inhabited Jesus was not a divine person other than the Father and the Spirit; rather, it was the divine attribute of the Father who lived in Jesus.

One of the two main antagonists of Christ’s correct vision in the 4th century was Apolinar de Laodicea (around 315-92), who reacted, in part, to other heretical movements, in his reaction to a vision like That of Paulo of Samsata, Apolinori argued that the Logos had assumed a human body, but not a human spirit. His opponents correctly replied that this theory meant that the incarnation would simply be the deity inhabiting a flesh without spirit or soul. Many Christians today fall into a similar situation, error in thinking that the spirit and soul of Christ are their divine nature; But that’s not true. The other heretic of this period was Arrio of Alexandria (circa 250-336). He denied that the Logos was the same as the Father and argued that there was a time when the Son of God did not exist.

In the 5th century a more precise Christology was established, but only after a long political and theological struggle. In fact, even before Chalcedon, there were councils seeking to understand the biblical data about the person of Christ. During this century, the most important of the early Church for the development of Christology, the theologians of Antioch, where Nestorio received his training, were very determined to live up to the full humanity of Jesus. Cyril of Alexandria (c. 376-444), perhaps the most important theologian he wrote about the person of Christ in the early Church, appreciated this concern, though he sometimes said things that seemed to contradict that belief. In fact, Cyril and the theologians of Antioch agreed for a while. Of course, the agreement was not complete; Cyril’s most extreme followers, such as Eutics, tended to “deify. “humanity of Christ.

All this shows that all theologians until now had a common belief in the two natures of Christ, yet their differences were in the quality or integrity of both natures in relation to the person of Christ, some insisted so much on the divine nature that there was little or nothing left of Christ’s human nature; others have done the opposite. Chalcedony seems to have successfully solved the problems that plagued the church for the first five centuries.

As the Christological crisis of the 5th century continued to intensifie, Empress Pulcheria and Emperor Martian convened a council in Chalcedon, which was closely monitored. Not only were some bishops admitted and others rejected, but some documents and others forbidden were admitted. In the Council of Ephesus (431) the volume of Leo, Bishop of Rome, was not allowed; but in Chalcedon, the Book of Leon was forbidden. It allowed that, combined with Cyril of Alexandria’s emphasis, a kind of common statement could be reached. Cyril, who died years before Chalcedon, insisted heavily on the union of the two natures into one?Unity?impeccable (in Greek henoosis ). The emphasis on both natures, the product of Western Christology (typical of Augustine and other Westerners), reflected an emphasis on the Lion, which also reaches the creed. In the central paragraph of Chalcedon, it reads:

Following the Holy Fathers, we confess to oneself, our Lord Jesus Christ, and we all unanimously teach that the same is perfect in divinity, the same perfect in humanity; true God and true man; the same with a rational soul and body; substantial with the Father in divinity and also substantial with us in humanity; like us in everything but sin; begat before the centuries, from the Father in divinity; the same in these last days, and for our salvation, born of the Virgin Mary Theotokos [?Bearer of God?] in humanity; one and Christ himself, Son, Lord, one; recognized in two natures, unmistakable, immutable, indivisible, inseparable; the difference in nature is not undone in any way by union, but by the distinctive character of each nature that is preserved, combining in a person and hypostasis; not divided or separated into two people, but one and the same Son and a begat God, Word, Lord Jesus Christ; how the prophets of the past and the Lord Jesus Christ Himself taught us about them, and how the fathers’ creed has been passed on to us.

This statement about the person of Christ remains a beautiful demonstration of orthodoxy, with which those who wish to remain Orthodox and faithful to the entire biblical witness must agree. He stood the test of time. It is true that the definition lends itself to different interpretations, for example, Catholic, Lutheran and reformed theologians have developed Cristologies that cannot be harmonized in certain respects. -Caledonian conflicts, there is no denying that some conflicts persist today, even if they do not have the political ferocity of the early Church. by Christ: “Who do men say I am?”

The proof that Jesus of Nazareth is completely divine, homoousious (a substance) with God, is so abundant that it is very difficult to sympathize with those who fight against this truth. If Jesus is not completely God, New Testament writers have tried to confuse and lie in the church (for example, see Phil 2. 5-11; Cl 1; Heb 1).

The prologue to the Gospel of John provides sufficiently explicit evidence that the Church can satisfactorily conclude that Jesus is “truly God. ” Consider the opening words: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. ” Later in the prologue, John makes a surprising point (perhaps the most incredible verse for any first century Jew): that “the Word became flesh. ” Word? in verse 1 it should be contrasted with? if that’s the case? in verse 14. Wasn’t the Word (Logos) made? in the sense of birth. Rather, the Word simply “was. ” Other passages in the Gospel of John only serve to confirm and reinforce this truth (John 3. 13; 6. 62; 8. 57-58; 17. 5; 20. 28). Also, when Isaiah saw “The King, the Lord of hosts? (Is it 6. 5) John quotes much of this chapter and then says that Isaiah said this – because he saw his glory and spoke of him [Jesus]? (Jn 12,41). In Isaiah we are told that God gives his glory only to himself; However, in John 17. 5, Jesus asks the Father to glorify him in his presence “with the glory that I had with you before the world existed”. If Jesus is not God, then not only is he deceived, but his request is an abomination.

In the Book of Revelation, there are also many places that demonstrate Christ’s divinity. In describing Jesus in the Book of Revelation, John clearly establishes a link between Jesus and Yahweh (the Lord):

“Me, the Lord, the first and the last myself?(Is 41. 4). ? Don’t be afraid, am I the first and the last and the living?(At. 1,17-18).

“I am the first and I am the last, and outside of me there is no God?(Is 44. 6). To the angel of the church of Izmir, he writes: These things say the first and the last, that he was dead and lived again?(Ap 2. 8).

“I am the same, am I the first and also the last?(Is 48:12). Am I Alpha and Omega, the first and last, the beginning and the end?(Ap 22:13).

These striking parallels leave little doubt about what Jesus himself believed he was: no less than Yahweh himself.

Jesus is not only divine, but also truly human. As Chalcedon says: “A true man; the same rational soul and body; [?] Substantial with us in humanity; like us in everything but sin?”Is his name? Christ Jesus, man? (1 Tim 2:5), who participated in “meat and blood” to overcome the devil with death (Heb 2:14). Does he look like us at all? (2:17), to the point of having been tested in all things in our likeness, but without sin (4. 15).

The test of Christ’s true humanity is as conclusive as proof of his true divinity. Being truly human, Jesus experienced physical reactions such as hunger (Mt 4:2), thirst (John 19:28), and fatigue (John 4. 6). She cried (11. 35), cried (Lk 19:41), sighed (Mk 7:34), and groaned (Mk 8:12). Like B. B. said. Warfield: “There is nothing left to give the strong impression that we have in front of us, in Jesus, to a human being like us. “

But because he had no sin, all his passions remained in perfect proportion and balance. He was properly angry when he was angry as well as completely happy when he was happy. Not only joy, but exaltation, not a mere irritated annoyance, but a furious indignation, not a mere passing piety, but the deepest movements of compassion and love, not a mere superficial anguish, but a deep sadness to death, [who still] never dominated it?(War Champion). All his affections remained in total submission to the will of his Father.

How can we understand that Jesus is fully God and fully man?One word: Incarnation (Lk 1:26-38). God’s greatest prodigy is the incarnation of the Son of God. Heaven has embraced the earth. Therefore, the Creator identifies forever with the creature. In the union of the two natures in the person of Christ, we see eternity and temporality, eternal bliss and temporal sadness, omnipotence and weakness, omniscience and ignorance, immutability and mutability, infinity, and O, as Stephen Charnock says: “May God on a throne be a child in a cradle; that the thundering Creator is a crying baby and a suffering man are expressions of such great power as well as such condescending love that he surprises men on earth and angels in heaven?

But what about the language that says Mary is Theotokos (God’s carrier)?The truth of this statement should not be rejected because of the way it was misinterpreted by Roman Catholics and used to venerate Mary as the “Mother of God”. The title “Bearer of God?” said something about Jesus, not Mary.

When the Son became flesh (John 1:14), he assumed a human nature, not a human person. Human nature subsists on the personality of the Son of God: “Not divided or separated into two people, but one and the same Son and only begotten God, Word, Lord Jesus Christ”. Theologians have called the incarnation of the Son of God a “hypostatic union. “The union of the two natures in one person means that when we talk about Jesus, we are not saying that his human nature did this or his divine nature did that. Instead, we say that Jesus did this or that according to his human or divine nature. Paul points this out at the beginning of Romans: “And his Son, who according to the flesh came from david’s descendants?(Rom 1. 3).

He whom Mary gave birth to was not merely human, nor human; he who was born of Mary was a divine person who possessed both a human and divine nature; this person is the Son of God, which means that Mary can be called, the bearer of God?as long as that means it’s clear. The title theotokos states that Jesus remained completely divine even when he assumed human nature. She does not say that Mary is worthy of veneration as the “queen of heaven” or as a co-mediator with Christ, as Roman Catholic doctrine teaches.

Most Christian theologians affirm the distinction between the two natures of Christ, but the relationship between these two natures has been the source of great conflicts between various theological traditions. At this stage, the calcedonium creed allows a variety of interpretations.

Reformed theologians cling to the ultimate theological that finite (humanity) cannot contain the infinite (divinity). This maxim is true for both natures of Christ, even now in heaven. That is why Christ has limits according to his human nature. He developed from childhood to adulthood and experienced the growth of knowledge appropriate to each stage of his life (Lk 2:52). He was to be taught by his father (Isa 50:4-6). According to his humanity, he should be satisfied that not everything had been revealed to him during his time on earth: “But on this day and this hour no one knows, neither the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but the father?(Mt 24:36). Did you learn obedience through suffering (Heb 5:8).

Since the relationship between the two natures of Christ has been hotly debated from Chalcedon, the Westminster Confession of Faith (8. 7) offers an explanation of the “communication of property”, which clarifies the previous point: “Christ, in the work of mediation, acts according to his two natures, each doing his own; However, because of the person’s unity, what is inherent in one nature is sometimes attributed in the scriptures to the person designated by the other nature. here, though. Although attributes of any kind can and are attributed to the person, the attributes of each nature cannot be attributed to the other nature. For example, Jesus did not die according to his divine nature, because death cannot be predicted, something that only human nature can suffer, to divine nature. Jesus died according to his human nature, but not according to his divine nature.

To get an idea of what confession means here, consider Acts 20:28: Take care of yourself and all the flock that the Holy Spirit has made you bishops, to shepherd the church of God, which he bought with his own blood . ? In this verse, the one person of Christ is called by nature divine. In other words, he is called “God” even though he is God and man, divine and human. However, being a Spirit, God does not have blood. Blood is just human nature, not divine nature. What the confession says is that because the two natures are united in one person, the blood (which is just human nature) is attributed to the one person of Christ (who in this verse is called or called ‘God’, although the name of God belongs only to the divine nature). Because Christ has two united natures, we can speak of the “blood of God”, since “what is proper to one nature is sometimes attributed, in Scripture, to the person designated by the other nature. ” The attributes of any of the natures can be based on the person of Christ, even when Jesus is referred to by name or in a way that is unique to only one of those natures.

Subordination: Jesus voluntarily submitted to the will of the Father. From Philippians 2: 6-11 the Son of God, surviving in the form of God, did he not judge usurpation equal to God?(Above), but stripped of himself, took the form of a servant, and obeyed the Father until the death of the cross (low), which in turn led him to exaltation, in which he is given the name above all name (high). All new Testament statements regarding subordination?From Christ (Jn 14:28) it must be understood in the light of the agreement between the peoples of the Trinity, by which the Son would take human flesh and be subordinate to the Will of the Father.

Impecibility: Would Jesus, once tempted, have the opportunity to sin?Theologians disagree on this question, but the answer should be “no. “There are two reasons why Jesus could not sin. First, if Christ could sin, then there would be a problem with the relationship between Christ’s human and divine will. The definition of the faith of the Sixth Ecumenical Council of Constantinople (680-81) states: “And these two natural wills are not contrary to each other as the evil heretics claim, but their human will continues, without resisting or reluctance, before subjected, to your divine and omnipotent will?The human will cannot be contrary to the divine will in Christ, but only subject to it. Second, by the unity of the persons, Christ could not sin without compromising God Can the human nature of Christ be sinful?(capable of siding); but because in his constitution he is man-God, he is therefore an impeccable person.

The Holy Spirit: If Christ was completely divine, why do we read so many references to the work of the Holy Ghost in him during his earthly life?, from the moment of the incarnation (Lk 1:31,35), through his baptism (Mk 1:10), his temptation (Ms 1. 12; Lk 4. 14), his preaching (Lk 4. 18), the work of miracles (Mt 12. 28), his death (Heb 9. 14), his resurrection (Rom 1. 4; 8. 11), until his ascension and induction. (Exit 45. 1-7; Acts 2:33), we discover that the Holy Ghost was a constant and inseparable companion of Christ.

Christ chose not to regard his equality with God as something to be exploited or enjoyed (Philippians 2. 6) Therefore, in total dependence on the Holy Spirit, Christ obeyed the Father perfectly, without attachment to his own divine nature. As John Owen argued, “Everything the Son of God has done in or about human nature has done through the Holy Ghost. “The Holy Ghost produces in Christ the fruit of the Spirit (Gal 5:22). Therefore, believers can expect not only a formidable savior, who has conquered the powers of darkness, but also a merciful, patient, kind and loving savior, because he is filled with the graces of the Holy Spirit. Because of this truth, Thomas Goodwin affirmed that the sins of God’s people drive Christ more to compassion than to anger. In fact, Goodwin adds, “if there were infinite worlds composed of loving creatures, there would be not so much love in them as in the heart of man Jesus Christ. “

Due to the entry of sin into the world by man, man must make reparation to God. But sinful man cannot repair the damage of his sin. A simple man without sin could only potentially give restitution to a sinful man. The repair of many men (? Like the sand on the beach?) Can only be done by the man-God, Jesus Christ, for the infinite value of his person. He is the appointed Messiah, the only one who can bring salvation to sinners through his death and resurrection. Peter recognized this great truth, to his great benefit. By faith, Peter confessed Jesus as the Christ, the Son of God (Mt 16:16). By vision, Peter now beholds the glory of God before Jesus Christ. Those who behold the glory of God before Jesus Christ in this life, by faith (2 Corinthians 3:18), can confidently trust to do the same in the life to come, in sight (5. 7). This is our hope; it is our joy. That is why the only hope for the church today is not a simple man, but the man-God, who asks you: “Who do you say that I am?

By: Mark Jones. © 2014 Ligonier. Original Ministries: A Summary of Orthodox Christology.

This article is part of the December 2014 issue of Tabletalk magazine.

Translation: Joel Paulo Aragono da Guia Oliveira. Critic: Vinicius Musselman. © 2016 Faithful Ministérium. All rights reserved. Website: MinistryFiel. com. br. Original: A summary of Orthodox Christology.

Authorizations: You are authorized and encouraged to reproduce and distribute this material in any format, provided that the author, his ministry and translator are no longer no longer modified and not used for commercial purposes.