500 years of Protestant reform

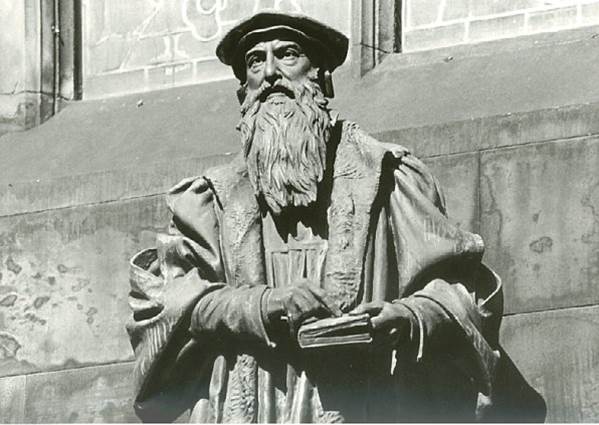

To celebrate the 500th anniversary of the Protestant Reformation, Return to the Gospel will present weekly articles and biographies of several reformers: Girolamo Zachi (January), Theodore Beza (February), Thomas Cranmer (March), Guilherme Farrel (April), William Tyndale (May), Martin Bucer (June), John Knox (July), Ulrico Zuonglio (hay), Joo Calvino (set)

- Historians are not sure whether it was in 1514 or 1515.

- Or sometime in the near future.

- When Knox was born in the small town of Haddington.

- Scotland.

- On St.

- Mary’s Street.

As the Rosalind Marshall biograph explains, much of Knox’s youth is unknown. He did not enter the history books until he was thirty years old, and how little we know of his previous life was in the annals of his contemporaries. He attended the University of St Andrews and successfully completed his studies, although there is no evidence beyond the word of Theodore of Beza, his contemporary, who considered him a distinguished scholar, and others called him?Knox ?, a degree reserved for those with academic knowledge. He probably spent some time as a local lawyer, too, but no one is sure.

The first thing we know about Knox is when he invaded the stage during some of the most tumultuous years in Scotland’s history. Knox became a Protestant, joining the group of George Wishart, a Protestant leader and Knox mentor who was later burned at the stake by Tenga note that when Wishart was traveling to speak, Knox came forward with a large double-edged sword. Did he do things like carry swords and more?Part of this was due to the time he lived and part of that was simply due to the fact that he was not a good man, at least not because of the way others perceived him.

As in the days when he had the rare opportunity to preach to Edward VI, king of England, and attacked the practice of kneeling over dinner, the context surrounding this sermon was a new Protestant influence on the Liturgy of the Church. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer had just published a new prayer book, the second common prayer book, because the first book had been rejected because it seemed very Catholic. The second book, which distanced the Protestant practice from Roman Catholicism, was the only manual of legal worship in the Church of England. but Knox hated people being instructed to receive bread and wine on their knees. He insisted that such an order could not be drawn from the scriptures. The day before he had an audience with the king and preached about the practice of kneeling.

Or when he wrote the “First Trumpet Blast Against the Monstrous Government of Women. ” The premise of the treaty was that women should not be leaders and there was more than one good reason for their argument. Mary I took the throne in England after the premature death of Edward VI. She was a devout Roman Catholic and was ready to nullify any Protestant victories England had won under King Edward. He was entering his fifth year of reign when Knox published the? First trumpet ring? and at his death in November 1558 he had murdered some 300 Protestants. Mary, the bloodthirsty, was a Jezebel, and did Knox want to discredit her right to rule? we understand this part. But as for her rhetoric, in her efforts to defeat the queen’s tyranny, she said nasty things about women in general, like: “Nature,” I said, “portrays women as weak, frail, impatient, weak, and silly. ” , and experience has declared that they are fickle, fickle, cruel, and don’t care about advice and regulations. And have men noticed these obvious flaws in all ages?

This argument is simply not valid (God made mothers to women, after all!). Unsurprisingly, his great treaty was unsuccessful, neither with Mary, nor with his Protestant sister, Queen Elizabeth, nor with the monarch women in Scotland, with Maria de Guise and with her daughter, Maria Stuart. He was surrounded by female leaders and yet wrote that. According to Marshall, this writing is no less unpopular in today’s Scotland, giving Knox a public reputation as “the first and most insulting male. “”country. com.

Then, of course, came that moment when he met Maria Stuart and made her cry. After the death of his mother, Maria de Guise, the Scottish Parliament made the nation Protestant. Maria Stuart grew up in Catholic France and returned as scotland’s rightful monarch, despite being young and widowed. Some thought it would convert to Protestantism; others, like Knox, feared that she would marry a Spanish Catholic, reverse Protestant progress, and end up repeating Mary’s bloodthirsty reign in England. He publicly criticized rumours about the wedding plans and was therefore called to a meeting with her.

According to the record, she was furious when she saw him and said, “I can’t get rid of you, I swear to God, will I be avenged?”But then she cried hysterically, in the presence of Knox, about forty, she cried so loudly and so loudly that the page ran to give her handkerchiefs. It was strange, to say the least, how Knox expected it to end. Once he calmed down, he uttered a few more words, concluding, “I am not my own master, but I must obey the One who commands me to speak clearly and not flatter the flesh of this country.

But then the situation got worse. After another brief conversation, Mary began to cry again, sobbed violently and was even comforted by others, Knox told the story, saying that she had to wait a long time in her presence as she tried to recover. Knox waited almost an hour, remaining uncomfortably silent with some other people until he told a group of elegantly dressed women that they would die and be devoured by worms. words, he said, “Think of a terrible death!? Will the dirty worms take care of this meat, although it was once very beautiful and delicate?

There are these examples and countless others from the days when Knox infuriating people, infuriating Catholics and Protestants, men and women, rich and poor, it seems that not everyone who knew him, at least at some point, liked him. it’s not an exaggeration. Most surprising of all, though, Knox didn’t care.

It is almost hard to believe how tireless his life has lived; he believed that God had called him to preach the truth, and that is almost exclusively what he was doing; opposing an accomplished culture of labels and flattery, Knox simply said how Marshall writes, “Knox was convinced that, as a preacher of God’s Word, he had been sent to offer spiritual guidance to all, no matter how important it was. “He was like an Old Testament prophet.

While I do not believe that modern Church leaders should model their discourse in Knox’s, and while many of their lives’ actions should not be imitated, their courage is what our attention requires.

Incredible is not what he said and when he said it, but the audacity that John Knox made him speak really believed that he would never die (John 11:26) and that his momentary afflictions prepared him for an incomparable and eternal weight of glory. (2 Corinthians 4:17), and that if he were to please man, he would not be a servant of Christ (Galatians 1. 10).

He lived in a reality that many of us share, but which many of us forget during adversity: if we are united with the glorious Son of God and filled with the eternal Spirit of God, and are declared irreversibly righteous and children by God the Father, we are untouchable, we will inherit the world, you know it (Matthew 5. 5). We will judge the angels (1 Corinthians 6,3). God knows how much hair we have on our heads (Matthew 10:30), and more than that, he makes everything that happens in our lives serve to conform to the image of Jesus (Romans 8. 28), and will we be afraid?Seriously, what can simple flesh do to us (Psalm 56. 4)?

We all know about it, but John Knox practiced this truth every day. He lived as if it were true, because after all, it’s true.