Translator’s Note: This text reveals crucial details about the plots of two of Dostoyevsky’s main works:?Crime and punishment? And the Karamazov brothers.

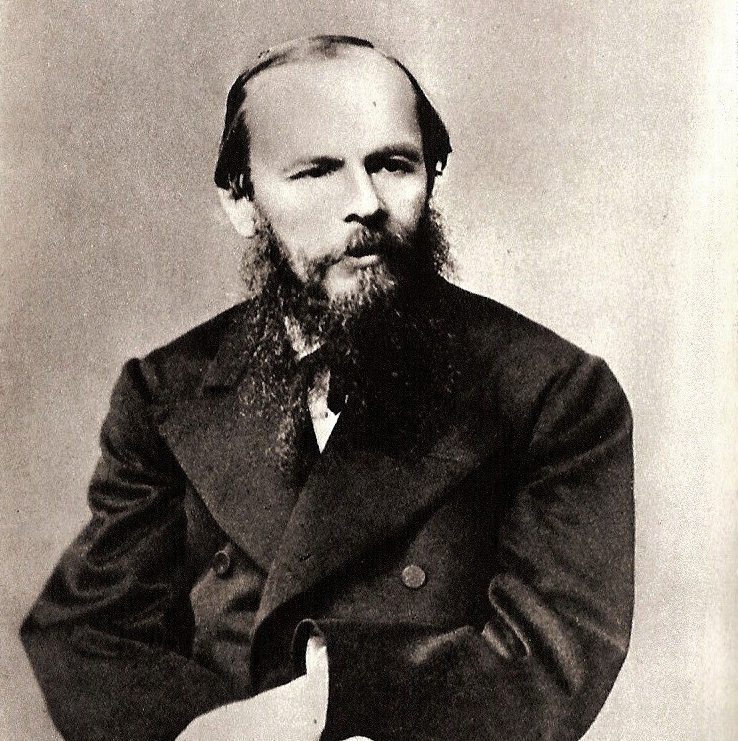

This year marks a century and a half since the great Russian novelist Fior Dostoyevsky introduced crime and punishment to the world (1866). As is typical of his novels, Crime and Punishment is not what can be called an exciting or animated reading. , I suppose, a ‘happy ending’, but it takes a lot of pain to get there, and even the end is painful. After all, it’s a Russian novel.

- Raskolnikov.

- The protagonist.

- Is a poor and melancholy student who spends too much time living in his own world.

- Rests in the world around him.

- Considering himself a superior human being who should not be constrained by the ethical concerns of the masses.

- Considers himself a great man.

- A benefactor.

- A charismatic leader.

Convinced of his superiority over the laws of God and man, Raskolnikov brutally murders a moneylender and his sister to steal their money, but ultimately because he believes he has the right to do so. you can’t fool your conscience that easily. He confesses to the crime and is exiled to Siberia, but there, accompanied by the nun Sonia, he finds peace and forgiveness.

Crime and punishment is rightly acclaimed for its psychological depth and realism, but there is another reason for its fame that makes it an inescapable reading, especially for Christians concerned about the devastating effects of moral relativism on the modern world. Like Alfred Lord Tennyson: In his epic poem In Memorian (published in 1850, but most of which was written in the 1830s), struggled with the implications of Darwinian natural selection more than a decade before the publication of The Origin of Species (1859), Dostoyevsky also, in Crime and Punishment, exposed the dangers and disappointments of Nietzsche’s superman theory for twenty years before introducing such a figure into the world in Thus spoke Zaratustra (1883).

Superman by Nietzsche

According to Nietzsche, is the over-the-top (German word for superman) someone who finds in him the courage to free himself from the chains of bourgeois morality?Ethical and moral standards that impose on us? For religion. Considering that Marx would repudiate religion as “the opium of the people,” Nietzsche saw it as an ethic of the slave, an instrument used by the weak to control the strong.

Without fear of religious codes and superstitions, does ubermensch surpass these artificial structures?goes beyond good and evil to affirm his desire for power. Only an individual freed from these structures can lead society into a glorious future. While it is not entirely fair to blame Nietzsche for Hitler, his theories have provided sufficient justification for totalitarian leaders of all political kinds to conceal their acts of injustice under the appearance of instruments for the advancement of civilization.

In Raskolnikov, Dostoyevsky introduces us to what would become a Nietzschean superman, someone who does not believe that the laws apply to him, although he certainly expects others to follow them. The fact that he feels the need to justify himself proves that he is an ethical being in which moral pretensions are linked. He may be considered immune to legal sanctions, but he cannot escape his own inner judge: the conscience God has placed in each of us. Raskolnikov knows that he has committed a crime and knowing him requires the existence of a supernatural pattern that is neither relative nor artificial.

Just as pain indicates something that is weakened in our bodies, guilt indicates something that is weakened in our souls. Even trying to convince himself of his superman status, Raskolnikov is deeply affected by guilt and remorse. A modern Freudian therapist would probably tell you that the problem is your fault, not him. The reality of his guilt lies in the fact that it contradicts moral relativism, the false belief that man can live, make decisions and prosper in a world beyond good and evil.

Resulting ideas

It is clear to me that Dostoyevsky considered part of his mission as a novelist to warn us of the satanic temptation of what the Nietzschean superman would be, I say this because, 13 years after Crime and Punishment, he threw The Karamazov Brothers, a masterpiece that refutes over-the-mensch in a way that no philosophical or theological treatise could expect to do.

A depraved and stupid madman, Fior Karamazov, is the father of three children who incorporate respectively the physical, intellectual and spiritual side of man: Dmitri, an impetuous and impulsive soldier; Ivan, an overly rational intellectual who rejects faith in Christ; and Aliacha, a pious monk who tries to help his father and his tormented brothers.

In the course of the novel, Fioror is killed and suspicions fall on Dmitri, but in the end, we discover that Fior was not killed by one of his legitimate sons, but by an illegitimate bastard, Smerdiakov. The revelation surprises everyone, including the reader, but nothing less than Ivan.

Notice: for many years, the grotesque Smerdiakov was a disciple of the nihilist Ivan. Ivan taught him how things are and that there can be no justice or truth in the world; on the contrary, once God is dead, everything is allowed. For Ivan, this Nietzschean vision of morality as purely relative and artificial is nothing more than an intellectual game; in fact, he suffers intense internal conflict over it, but sees no need to implement his academic theories.

This was not the case Smerdiakov. Al dollars to his half-brother, takes everything Ivan says as the truth of the gospel, and builds his own twisted worldview around him. If Ivan is right and morality is simply relative, then why shouldn’t Smerdiakov?behave exactly like Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment? In other words, why shouldn’t he commit a crime for his own good?If you are not subject to any moral standards or code of ethics, what will prevent you from killing the parent you hate?

The modern Nietzschean who reads The Karamazov Brothers is likely comforted in concluding that Smerdiakov has distorted and perverted Ivan’s nihilism. But that’s not how Ivan gets Smerdiakov’s proud and un excused confession about how and why he killed his father. Ivan sees that his theories are not simply imperfect; are false, evil and inherently destructive.

Dostoyevsky forces Ivan to see the fruits of his beliefs, to see what the true super-mensch is like, not beautiful, tragic and noble (like Napoleon in exile), but vile, petty and grotesque. Because of his self-knownness, Ivan abandoned his atheism and embraced the God he had once rejected. Ideas seem to have consequences.

Not free to fall

Our time may be considered radically democratic, but we are not free to fall into the deceptive rhetoric and utopian promises of over-mensch, on the contrary, we are not free to become one, so beware and pay attention to Dostoyevsky’s warnings: that they were intuitive enough to see the dangers behind a theory that Nietzsche would soon propose.

There is a presumptuous, evil and resentful Raskolnikov or Smerdiakov in each of us who struggles to get out.

By: Louis Markos. © 2016 The Gospel Coalition. Original: Dostoyevsky v. Superman.

Translation: Leonardo Bruno Galdino. © 2016 Faithful Ministério. All rights reserved. Website: MinistryFiel. com. br. Original: Dostoyevsky vs. Superman.

Authorizations: You are authorized and encouraged to reproduce and distribute this material in any format, provided that the author, his ministry and translator are no longer no longer modified and not used for commercial purposes.